I’ve been in Brooklyn this week, and Manhattan.

My

update is that the city and its boroughs have been damaged in a

thousand tiny ways that I newly noticed — as if the population has been

attacked by an enemy so clever that it arranged for each minuscule

attack to go unnoticed, though the cumulative damage would be

devastating:

Autistic Reactions are Being Normalized.

I’ve

written in my essay “Are Lipid Nanoparticles Subtly Changing Human

Beings?’ about the fact that mRNA vaccines are designed to cross the

blood-brain barrier and that thus they can cause, as Dr Chris Flowers of

the WarRoom/DailyClout Pfizer Documents Research Analysts puts it,

brain damage; as well as causing neurological damage.

This damage can be florid — there are many reports of utterly changed

personalities, of people suddenly raging, of accidents caused by road

rage, and of loved ones who can no longer moderate their personalities

or responses.

German neurobiologist Dr Michael Nehls, in his important book The Indoctrinated Brain: How To Successfully Fend Off the Global Attack on your Mental Freedom, explains

that the damage to the brain from mRNA vaccines, “lockdowns”, isolation

and propaganda, can be physical as well as psychological.

I

noticed that all around me, in heavily vaccinated Brooklyn, many people

seem now to have lost the ability to “tune in,” in a subtle way

socially, to others. Many people seem to have lost the instinct for the

rhythmic dance of conversation and even for mutually responsive body

language. Thus, many normal-looking, healthy-looking people with whom I

crossed paths in Brooklyn and New York, seem now to be slightly “on the

spectrum”, in far greater numbers than I had experienced before 2020.

We

know that this change in the brain post-2020 can be negative. Many of

us are aware that vaccinated or “lockdown-y” and “mask-y” people can

erupt startlingly in rage, or say awful things to their friends and

loved ones, and thus reveal in a dark way that their prefrontal cortices

are not modulating their impulses normally.

But what I experienced this past week was that many people seem now to have lost modulation — in a positive direction as well.

Here is what I mean: there were two beautiful blue-sky days, after endless wet overcast days of polluted or whited-out skies.

The

temperatures suddenly rose, humidity was low, the sun actually shone,

red and purple tulips and yellow forsythia bloomed, and narcissi,

planted in scruffy dirt squares cultivated around the urban trees,

lifted their white-and-orange faces. Magnolias languorously exposed

suede-glove-like white-pink blossoms; cherry trees erupted in clouds of

rose-colored confetti.

Of

course, we went to Prospect Park, which looked, blessed with Spring and

sunlight, like a 19th century European colorized postcard. There were

the perfectly symmetrical paths, the noble bronze statues of

now-forgotten figures, and the turtles sunning themselves on the exposed

rocks of the elegant lagoons.

It was magical, and people of all kinds crowded in, children and dogs in tow, to enjoy the delight of it all.

Then

I noticed the weirdness. Random people kept coming up to me — our dogs

were the initial reason for the connection — and just launching into

cheery monologues.

It

was fun at first. I heard about this one’s dog’s rescue, and what the

dog now ate, and how much the dog liked to sleep, and how other dogs

related to her. Then I heard about that one’s scholarship to a

prestigious economics school, and the startups he had funded, and the

fact that he had decided that relationships were too much trouble so he

had gotten his dog (details have been changed to protect identities).

There were many bulldogs named Lola. There were many cockapoos named

Max.

It

was nice at first to have perfect strangers be so chatty and

informative. But by conversation markers at ten minutes, then at

fifteen, then at twenty, I noticed that the usual dance of human

discourse was broken. It was happy monologue after happy monologue — no

questions, no curiosity, no externally-oriented interlocution at all;

not even that self-conscious, belated, “But enough about me. How long

have you been in the neighborhood?”

There was little self-awareness, it seemed, that another person was even present.

Could

this be due to social media? All these people were younger than I;

maybe that’s how younger people make friends now, I wondered?

Broadcasting entirely in the “I”, trained to do so by one’s posting on

socials? Or could this be due to long isolation?

Or was this odd verbal pattern — possibly a manifestation of something physical?

Whatever

the cause, I noticed this emotional obtuseness with the parenting going

on around me, as well. I’ve noticed earlier that parents post-2020

don’t seem to have that intuitive sense of their kids’ being in physical

danger; that they allow their kids to race anxiously to catch up with

them in crowded, dangerous settings, and let the kids wander off to

climb over dangerous structures.

By

the same token, I noticed this week in Brooklyn that parents in their

30s and 40s seem to have lost all sense of being tuned in to their kids’

nutritional needs. I was aware that the bodega where I get my coffee in

the morning is thronged with lower-income kids buying Doritos and grape

soda for breakfast, and I thought that that was just due to the tastes

and budgets of kids. I myself as a child would sneakily consume a

handheld pie and a chocolate milk, rather than my mom’s hippie paper-bag

packed lunch — with its strange cheese-chunk sandwiches made of thick

whole-grain bread — whenever I was rashly given a quarter.

But now, it’s not just the kids. Parents

at the bodega urge their kids to get Hershey’s bars or potato chips for

breakfast. And this trend is widespread. I saw this exact same lack of

interest in the kids’ nutrition among many of the affluent Brooklyn

parents: wealthy parents urging their small kids

to choose cake pops or chocolate donuts for breakfast. It seems as if

the truisms of parenting and nutrition in my generation, which included

training in delayed gratification — “You can have dessert after you finish your dinner” or even the stern dictum, “Just one treat a day” — have gone right out of the window.

These

parents acted as if they could not wait to get the kids onto their

sugary treats, and then they themselves got fixated on their phones. The

kids ate their donuts and gazed off into middle distance, and the

parents stared at the screens.

No chat, no sustained conversation, no verbal play, no silliness, no making of faces.

It’s not just nutrition that is being neglected by moms and dads now. It’s all interaction.

I saw lots of affluent younger moms pull a plastic covering, like a clear Zip-Lock bag designed for baby humans, right over

the toddlers in their strollers — rain or shine — and, as if the moms

have closed up a business venue for the day, they’ll then wedge their

phones against the push-bars of the stroller and walk

the stroller, with their eyes glued to the screens. No peeking, no

peek-a-boo, no excited high-pitched commentary about passing doggies and

trees and birds.

Silence.

All of these are the kids then whose faces are blank when they meet the eyes of strangers.

So

a set of autistic-type reactions, and an overall blunting of emotional

affect and nuance, are being inscribed by these interactions, into the

next, otherwise perfectly healthy, generation.

Is

this lack of concern by the parents for the kids’ nutrition — and even

mood, because heaven knows there will be a sugar crash in their near

futures — and language skills, and ability to connect, and affect - now

cultural?

Or

is this complete detachment in parents, from the nutritional and

emotional as well as the physical wellbeing of their children — be

perhaps partly now physical?

If

you had wanted to ruin a great city, the center of a great civilization

— change human interactions just a little bit; so that no one cares

that much, or can tune in that well, to anyone else; and especially, so

that no one really cares to tune in to the next generation of that

fragile civilization.

****

Illegal Surveillance is Being Normalized

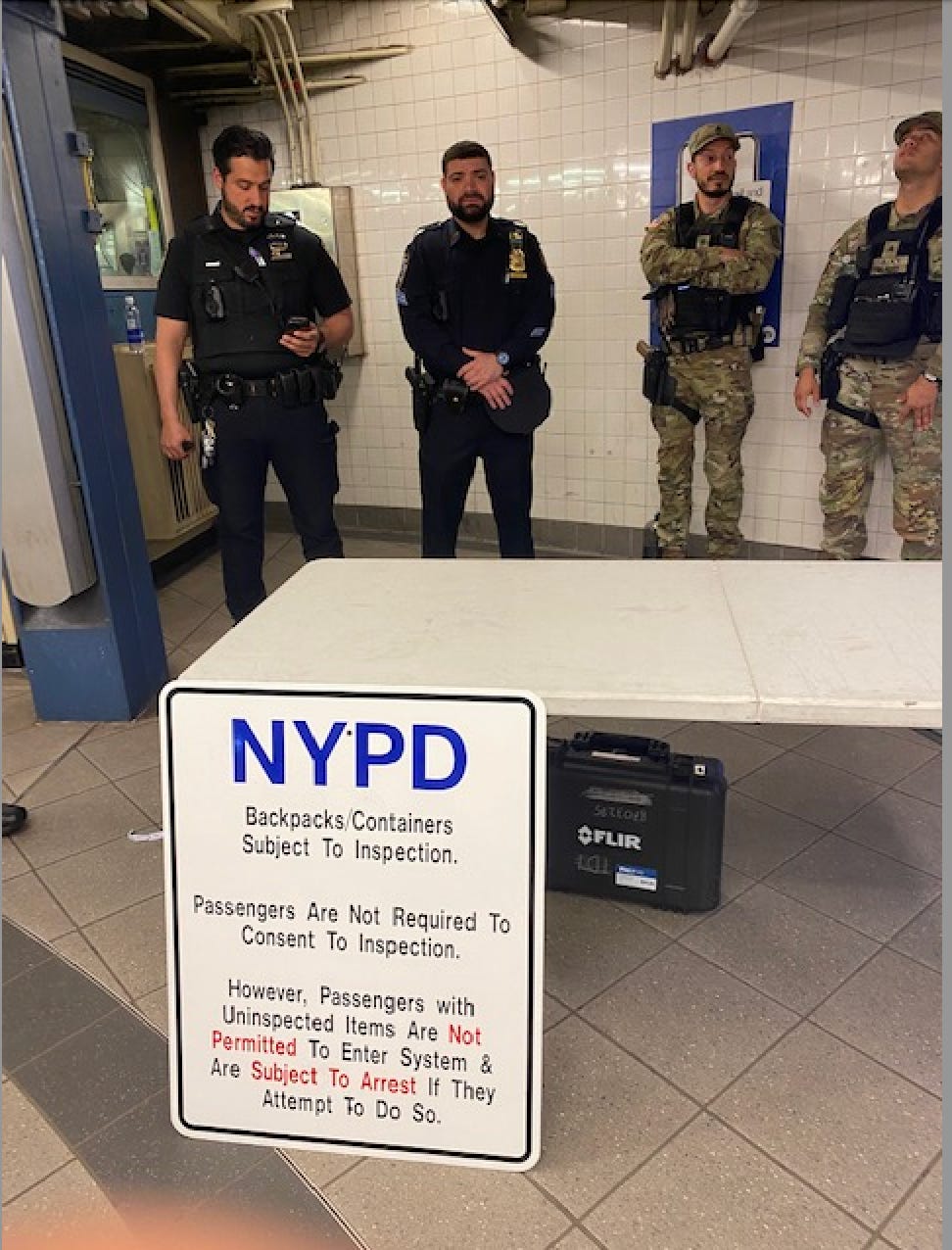

I went into the subway at a major transfer station, where multiple subway lines converged.

At

the entrance, looking detached and even sheepish — one cop was on his

phone — was a phalanx of about twelve New York City police officers. A

few National Guardsmen stood with them, as Gov. Hochul had promised and

warned — looking bored.

In

front of the men was a sign warning that everyone who entered the

subway needed to consent to have his or her possessions searched if

requested by NYPD. If you are not willing to consent to that, the sign

warned, don’t enter the subway; you are subject to arrest.

I asked — politely — something like, “What about the Fourth Amendment? You need a warrant, and probable cause, for a search."

The

cops looked jaded, even pained. They had surely heard this question

many times before. I know that they - or their colleagues — had heard

it, because I for one had asked the same question in 2008, during the

“Global War on Terror”, when NYPD had been stationed exactly similarly

at the entrance to West Fourth St station.

In fact, it looked as if the very same sign had been retrieved from storage, and dusted off, 16 years on.

One

of the NYPD officers, trained with exactly the same manual in use

during the same kind of effort to remove our Constitutional liberties in

2008 as now, gave me the exact same soundbite:

“The MTA is private”.

As in, the Constitution does not apply to a private enterprise.

In

2008, I’d looked into this answer, and had found that the MTA is not

private by any means. It is a “public-benefit corporation chartered by

the New York State Legislature”, with a governing board, that accepts

billions of dollars in public funding. There is no law that holds that the Constitution is moot when you are in the subway system because “it is private”.

The

NYPD officer’s answer to me in 2024 (just as the NYPD officer’s exact

same answer to me in 2008) was a gaslighting fib, handed down no doubt

from highers up. The bag searches, controversial enough when introduced,

were in fact illegal per the Fourth Amendment.

But a 2005 “exception” to the Fourth Amendment, permitted by a “special

needs” carveout justified by the then-”War on Terror”, had been the

loophole created in the Bush era to justify them. If the cops had

answered honestly, though, now, citizens would no doubt have pointed out

that the Global War on Terror is over.

As

I’d begged the nation to realize at that time, the restraints against

liberties rolled out under the guise of fighting the “terror threat”

would never be sunset-ed, and they’d eventually be used against Americans, willy-nilly.

And

now, here we were again, opening our bags in violation of our Fourth

Amendment rights, for literally no good or lawful reason.

This

time, though, our spirits appeared to be well-nigh broken, as it seemed

that this time around, no one was even bothering to ask the questions.

###

Is it 1933 Still/Again?

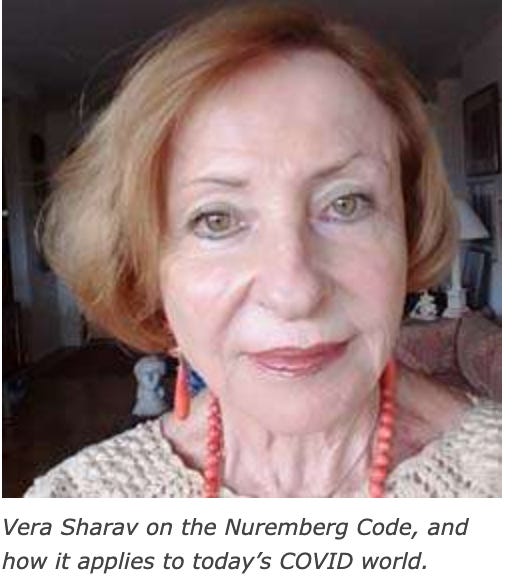

I

was honored to have lunch, then, with the remarkable freedom movement

leader, Vera Sharav, and our mutual friend, whom I shall call “Anna.”

Ms

Sharav is a longtime activist against eugenics in the biomedical

establishment. She should know eugenics when she sees it: born in

Rumania in 1937, she is also a Holocaust survivor.

She

produced the extraordinary documentary “Never Again is Now”, which

makes the case that the parallels between 2020-present and the early

years of the Nazi ascendancy, are undeniable.

Because she has stood firm in warning the West about these parallels, she has been reviled in many quarters.

The

day remained pristine and blue. A gentle sun warmed us. We sat at the

outdoor tables of a trendy restaurant, and admired the arches of Lincoln

Center across the street.

“Anna”

recalled later that that restaurant had not allowed her to enter,

during the vaccine-discrimination years in Manhattan. But they’d been

“not awful” about blocking her from their interior then, and we laughed

ruefully about how we were grateful for such appalling leniencies.

I

admired Vera Sharav at first encounter. These days I especially admire

anyone who insists on attending to the dying arts of civilization.

Her

self-presentation was beautiful — and few people bother to dress

beautifully these days. She wore a deep taupe sweater of fine wool,

which exactly reflected her sparkling hazel eyes. A lighter taupe

sweater, with elegant lines, draped her shoulders. Her skirt was olive

green. She wore eclectic cats’-eye and topaz golden rings on her

fingers. These picked up the golden and light brown and olive hues in

her clothing. On her head she wore a biscuit-colored cloche hat, with a

russet band.

I

felt an instant sense of connection. Ms Sharav is Rumanian, as was my

late father; and Ms Sharav looked a lot like many of my elegant,

high-cheekboned relatives from the Rumanian side.

As

always these days in New York, in dissident circles, our collective

conversation started with new deaths and disabilities around us.

A

friend in his late forties had had a heart attack; a magnificently

healthy man. Two people my age, whom I’d know from my extended social

circles, were dead. Five students from an Ivy League university with

which I’d been involved, were dead; in one year. Two friends of “Anna’s”

friends, healthy women in their fifties, had died in their sleep.

The toll, the toll. And the silence.

I

asked Ms Sharav from where her courage came. She answered something

like, “What can they do to me now?” She also explained that she did not

feel “survivor guilt” — an issue about which she is often asked. Rather,

she explained, she acts as she does because feels a sense of

responsibility. She had the chance to have a life; she survived; and she

feels a duty to warn people now of fascism descending on them, so that

they can prevent the fate that destroyed so many of those around her in

her childhood.

We moved on, as humans do, to happier subjects.

Mussels

in white wine-and-butter sauce arrived. The accompanying “frites” were

lovely and crunchy, surrounded by their Belgian wrapper of white paper,

and arranged vertically inside their traditional steel cup.

The

scent of the wine-and-butter sauce was intoxicating; flecks of parsley

floated on the surface of the broth, and Anna and I both dipped our

spoons.

We

enjoyed, after the meal was over, camomile tea, and espressos in little

white cups. Well-dressed men and women chatted all around us. Traffic

gently blared. Pigeons scurried around the statue in the center of

Broadway.

All was — normal?

And yet. And yet.

When

a cookie with ice cream and a lighted candle arrived — it was to be Ms

Sharav’s birthday the following day — wishes of “Happy Birthday!” came

from the nearby tables.

It

all seemed achingly like the “before times.” I gazed across the street

at Lincoln Center, where I had attended operas and concerts. I had worn a

tea-length maroon velvet gown, as I recalled, once, long ago, to an

opera there. Had the opera been “Carmen”? I’d been escorted by a former

partner, a man in the theatre world, who was now dead. He’d worn a

camel-hair jacket, an open white shirt. It had been an exciting Spring

evening like this one.

The

crowds at intermission had thronged the bar area for their aperitifs,

greedy and excited. I had admired at that time the red carpeting on the

dual sweeping staircases, the vast showy 1960s-era chandeliers, the

towering Chagalls.

We had all felt the fizzy euphoria that this was high culture. Ours was

high culture. We had all felt what we thought of as our specialness,

for knowing and enjoying the arts in this elevated, civilized way.

But the scene focused in again to the present.

Vera Sharav was explaining that she is now “banned” in Germany — she cannot even travel to Europe, and cannot visit Germany.

Why?

She is on a list. She could be arrested or fined if she did so.

A list of what? I asked.

Of people who engage in — criminalized criticism of the Holocaust.

The

Holocaust survivor would be arrested by the German state, for the crime

of warning others about the possibility of another Holocaust.

“They don’t see the irony”, she said drily.

Human and Child Trafficking: Being Normalized.

I was on the subway, then, heading South.

I

was starting to enjoy being back in the rhythm of movement around the

city, that you feel once you have become “a real New Yorker.” The

familiar stops whizzed past us: West 4th Street, Wall Street… Atlantic

Avenue…

A

very young woman made her way through the car. She looked to be about

sixteen, and appeared to be from a Central American country. She wore

clean tight blue jeans and a pink T-shirt, and she had a big, heavy,

apparently sleeping baby strapped to her back with a wrap, as tribal

women in Central America carry their babies. The child, its head

covered, did not move.

The

young woman carried a cardboard tray of packaged candies. “Quieres

chocolate?” she asked each passenger, in Spanish. It was about two

o’clock on a weekday.

I

had seen her before, many months earlier, on the same subway line, and

had been struck then at the fact that a young woman who looked like a

teenager was selling candy on the New York City subways, and was doing

so in Spanish. She left the car at the next stop, dangerously exited

with her baby into the oncoming crowd, and then re-entered the next car.

Who

was this person who looked like a teenage girl, doomed to peddle

candies on the MTA, all day long, month after month? If she was indeed a

minor, why was she not in school? She had no bag; nothing that

contained food for her baby; no diapers, no purse.

Who was looking after those items for her?

This did not seem like a business enterprise a teenaged mom would launch on her own. If not, was someone running her?

After she left the car, eventually, a small boy appeared in our subway car.

He also started to peddle candies to adult strangers. He looked to be about seven or eight years old.

He seemed to be completely alone.

He

too looked as if he was from a Central American country. He looked very

well groomed as well. He had despair in his face, and strain, and he

looked exhausted and traumatized.

I glanced around the entire car to see if his parent or parents were nearby. For that matter, was any adult taking care of him?

There was no adult anywhere near him.

He was entirely alone in our subway car.

Any stranger could have grabbed the child by the hand, and made off with him at the next stop.

I sat down gently next to him.

“Tienes padres aqui?” I asked.

“No,” he replied, with a look of anguish.

“Tienes un adulto contigo?” I asked further, in my bad college Spanish.

“Abajo,” he said, which made no sense to me. “Below.” Perhaps on a lower level of the subway?

Then he said, correcting himself, “En mi casa.”

Then,

I suppose, he felt that he had said enough, or perhaps too much, as, at

the next stop, he fled out of the open subway doors. He melted, still

entirely alone, into the surging crowd — of good people and of bad

people.

The other passengers, who had observed this exchange, looked away now, or looked at their phones.

An

older gentleman scolded me for my concern. “Of course there is an adult

around somewhere,” he said irritably. “He’s working, so there is going

to be an adult somewhere working him.”

The man actually said, “working him.”

The man spoke as if — this

was now normal. As if I were a meddling Karen, overreacting for

worrying about a young child on the subway who was completely alone

during a school day, laboring; who could be prey to any passer-by.

I

called 911 from inside the subway car. To my amazement, I got about six

minutes of a sound like a fax machine, in between recorded

announcements, first in Spanish, and then in English. The fax

machine-like sounds, the recording explained in English, were for the

benefit of “deaf callers.”

I

imagined desperate citizens of New York dialing 911 as intruders

mounted the stairs in a home invasion, or as some loved one lay unmoving

on the sidewalk, felled by a stroke or a heart attack.

This is what the caller would get:

Recorded greeting — fax machine sound — recorded explanation that the fax machine sound was for deaf callers —

Recorded greeting — fax machine sound — recorded explanation that the fax machine sound was for deaf callers.

This went on and on.

I thought of scared people in trouble around the city, desperate for Emergency Services to pick up.

I started to speak at last, when a human finally got on the line; but the call was cut off by the subway’s interference.

About

ten minutes later, I arrived at my final destination. Having left the

subway station and reached the sidewalk, I called 911 again.

I

went through the agonizing cycle again, of greetings in Spanish and

English, and then of fax machine-like sounds, and then of the recorded

explanations about the fax machine-like sounds being for the benefit of

“deaf callers.”

This

new system — and it was new; 911 in New York City used to be

professional and efficient and very quick — seemed now almost to be mocking us, as vulnerable people in a big city. It felt as if we were being trolled.

How would the “deaf callers,” I wondered, as I waited on hold — hear the fax machine-like sounds?

And — given that this was adding six minutes to emergency services’ human response to everyone who dialed in — could it be wise to create a separate line for the “deaf callers?”

At last the 911 dispatcher answered.

She took my description of the child and of the situation, said the case was now in the system.

But then she said:

“Is this at Franklin Avenue?”

Bergen Street Station had been the stop where the child had fled.

Franklin Avenue, in contrast, was the stop far down the line, where I was located as I made the current call.

But —

I hadn’t mentioned Franklin Avenue.

#####

Injuries to privacy.

Mass surveillance.

Damage to the Constitution.

Harms to children.

Erasure of the lessons of history.

I believe that New York City and its boroughs can some day be reborn.

But

before they can, they have to notice what has been done to them; how

they are suffering injuries - to everything that makes a civilization

strong, and protective of the vulnerable —

And they have to face the fact that these injuries to them, are from a thousand tiny cuts.